By: Rainer Kattel and Erkki Karo (Ragnar Nurkse School of Innovation and Governance, Tallinn University of Technology)

(This article was orginally published online on January 4, 2016 by The Institute for New Economic Thinking.)

For most economists and indeed for social scientists in general such a question induces shudders as already asking this seems wrong – aren’t governments more prone to failures than markets, and aren’t governments supposed to provide basic and stable institutions for markets to function?

There is, however, a growing interest in what is called public sector innovation both in academia and perhaps even more so among policy makers, for a number of reasons. First, innovation has become a panacea in many policy arenas: it is supposed to deliver not only economic growth but also better health and social care, more efficient energy systems, etc. In essence, the entirety of public sector activities is looked at through the lenses of innovation: innovations can take place in government daily functions (e.g., secure electronic signatures for contracts, adoption of new policy or service delivery processes) and innovations in markets can be supported through government policies (e.g., support for SMEs in hiring engineers that leads to innovations by these SMEs). Second, these lenses become even sharper during times of austerity – what could sound more appealing during a budget squeeze than “increasing productivity,” or delivering “more with less” in the public sector? Third, Mariana Mazzucato, Fred Block, and others have shown that governments have been hugely important over the last half a century if not longer in paving the way (via funding, regulating, and procuring) for most fundamental innovations of our times (such as the internet). In our own country, Estonia, bureaucrats are building a government start-up-like service, called e-residency, which is available to everybody globally and tries to make national borders and nationality-based public services a thing of the past. Thus, to ask whether bureaucracies can innovate is not so far-fetched; on the contrary, it seems highly pertinent that we understand how bureaucracies innovate.

So, what makes bureaucracies innovative? Most existing research on this specific question focuses either on the individual level (public entrepreneurship) or institutional level (innovation systems, social innovations) seeking either psychological/individual or cultural, regulatory, or similar determinants of innovation. Yet, private sector innovation studies largely concentrate on firms as the locus of innovation: organizations are the environments where individual and institutional determinants combine in complex ways and lead to different innovations.

In our recent paper, supported by an INET grant, we try to re-invigorate organizational-level analysis on what makes bureaucracies innovative. We show that this question can be tackled in two different ways that provide us with a unique view of innovative bureaucracies as highly diverse and dynamic organizational environments. First, what kinds of organizations are innovative in the public sector (organizational view)? And second, what do these organizations do (functional view)?

Organizational view

Perhaps surprisingly it is not public administration that has provided the most interesting answers to the question of what kinds of organizations innovate in the public sector but rather evolutionary economists. The answers evolutionary economists have provided fall, roughly speaking, into two streams.

First, a number of evolutionary economists have shown that expert bureaucracies have been highly successful in delivering industrial development and economic growth. This research originated from groundbreaking works on the rise of East Asia (by Chalmers Johnson, Peter Evans, Robert Wade, and others) and sees at the center of innovative bureaucracies politically relatively central yet autonomous agencies manned with specialists and engineers, functioning as a meritocracy, while also having good feedback-links with business actors. Such agencies – like the famed MITI in Japan or numerous US military agencies in post-WWII era – were both powerful and smart enough to direct the industrial investments and technology efforts of private or semi-private organizations (firms, universities), designing and using a variety of policy instruments from technology transfer to preferential interest rates to procurement of innovative solutions.

Second, relatively recent stream of arguments focuses on peripheral, agile, and smaller agencies (like SITRA in Finland; see research by Dan Breznitz). These agencies experiment with new policy ideas rather than invest into private enterprises. In short, they try to understand how governments need to change within and how they can support innovation in markets given the uncertainties characterizing new and emerging technologies (such as biotech, artificial intelligence, etc.) and given the increasing financialization and dominance of global production and innovation networks that seem to challenge the feasibility of any national or regional policy efforts. Today we see that emerging innovation labs, or i-labs, take a similar position within many public sectors across the world. Mindlab in Denmark and Nesta in the UK are examples of i-labs consciously operating under different rules than typical civil service organizations: these are small organizations with low funding levels and diverse sources of funding, and they are typically engaged in short term projects and relatively removed from political leadership. The idea is simple: create spaces within the public sector to experiment and take risks (see here for our recent study of i-labs). We call them experimental organizations.

The debate on the role of the state in innovation often gets stuck trying to find the definitive answer and policy prescription to the question: should we still stick to modernizing meritocracies, or move radically towards experimental, start-up like governments?

Interestingly, Max Weber, father of public administration research, described both types of organizations a century ago and crucially saw in their interplay or complementarity one of the key sources of rejuvenation and change within the public sector. Weber described experimental organizations as charismatic organizations based on the values and personality of its leaders; these are organizations that develop their own rules, principles, mores, and values. We call these Weber Type I organizations. Weber, famously, also described expert organizations, or classic bureaucracies; in his view, such hierarchical merit-based organizations that function based on clear rules (laws and regulations) and hire people according to their skill levels (often through an exam system) delivered very well efficiency and effectiveness both in private and public sectors. We call these Weber Type II organizations.

A somewhat closer look at the history of innovative bureaucracies shows that, especially since the early days of the 19th century, many such organizations had a intriguingly similar development path, particularly in Continental Europe. If we look, for instance, at such diverse organizations as the ones in charge of developing railways (e.g., Verein Deutscher Eisenbahnverwaltungen) or banking systems (e.g., Reichsbank in Germany), publicly supported cartels, and industry associations in most Continental European countries, we see a similar pattern. First, these organizations are born out of private initiatives and typically had industry needs at their core (seeking to ensure Schumpeterian monopoly rents from innovations) and hired professional experts from newly minted technical universities or the public sector. Second, in time many of the functions these organizations performed and the way they organized these functions became socialized and institutionalized into ministerial departments and public sector practices in general (or, as in the case of cartels, became effectively outlawed). That is, these organizations and functions became more public in nature and moved into more central positions in governance systems and thus became more hierarchical.

In essence we can argue that the history of innovative public sector organizations starts from a Weber Type I organization that is dynamic, innovates often in policies and regulations, and resides outside of typical government operations, and then moves then to a Weber Type II organization that is professional, and centrally governed with substantial funding and policy means. The cycle starts anew as new techno-economic opportunities and socio-economic needs and issues emerge that demand experimental solutions from the public sector (i.e., Uber and the likes are experimenting with new standards for transportation that may in turn become the basis of public transportation systems in smart cities of the future). Of course, the socio-economic and technical changes also change the fundamentals of expertise and meritocracy: if “classic” Weberian expert bureaucrats (in type II organizations) of the post-WWII era needed generic social and managerial skills (in languages, law, accounting, or planning), a “modern” Weberian Type II bureaucrat is increasingly expected to at least understand coding, change management, design etc.

These are, clearly, ideal-typical organizations; in real life there is a more granular morphology of such organizations, as shown by Henry Mintzberg. However, the Weberian dichotomy helps us to see the big picture, namely that policy and strategic experimentation and implementation may require different organizational dynamics and routines. Successful polities require flexible structures of governance where experimentation and drive for efficiency are of equal importance.

Functional view

What should then these Weber Type I and II organizations do? What is the function of innovative bureaucracies? Again, looking at the history of how governments have grown into innovation actors, we can differentiate at least six types of public sector innovation functions (changing technological needs and demands of the future can make some of these functions obsolete or complement them by others). These can be performed by either Weber Type I or II organizations, but in most cases we can witness a shift from Weber Type I organizations to Weber Type II as specific functions tend to emerge through economic or political pressures for change (often first as private initiatives that get copied or socialized by the state). These functions are:

- Public investment into science, technology, and innovation: both in the form of basic and applied research, this type of public sector innovation function is perhaps best exemplified by the iPhone: as Mazzucato has shown, the iPhone “houses” at least 13 key technologies developed with public money. In most countries we see both Weber Type II organizations (ministries) and Weber Type I organizations (DARPA-type agencies) carrying out this function.

- Public procurement of innovations: many of the solutions in the iPhone came to fruition also with government setting clear demands on new technologies and products being developed, as shown by the works of Linda Weiss and others. Again both Weber Type II organizations (ministries) and Weber Type I organizations (new procurement agencies combing the demand of different policy domains to test and design different procurements processes) may carry out such function.

- Economic institutional innovations: these are new institutional solutions that aim to change the economic rules of the game, e.g., the invention of the central bank that played a huge role in Germany’s rise in late 19th century, as argued by Piero Sraffa. Most would consider central banks as still more independent and different from traditional Weber Type II organizations (ministries of finance) but still rather “traditional” in their roles, especially as they are being pressured to reinvent themselves (in Weber Type I style) to tackle the increasing complexity of global financialization and the emergence of alternative currencies and technologies (blockchain, crowd-funding) that seek to provide alternatives to traditional public sector authority-based financial systems.

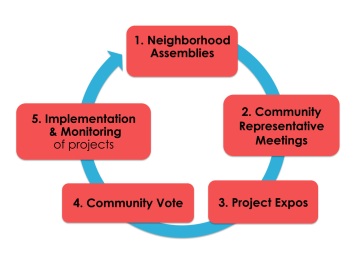

- Political institutional innovations: these are new institutional solutions that aim to change the political rules of the game. Alexis de Tocqueville admired more than 150 years ago how small New England townships were functioning well without central administration. He called this an innovative solution in comparison to French centralized administration. Also, today governments are constantly seeking to find a balance between more centralized/meritocratic political institutions (from judiciary to parliaments) and experimenting with more co-productive/participatory systems for legislation (i.e., constitution drafting in Iceland, different approaches to regulate drones, self-driving cars), budgeting (participatory budgeting) etc.

- Public service innovations: these are efforts to significantly change the way a service such as education or health is delivered. On the one hand, most countries try to maintain public trust in and legitimacy of classic Weber Type II organizations and to squeeze maximum efficiencies while new ICT-based solutions and services are being developed by other public sector organizations, often i-labs, or by start-ups that could also lead the way for socialization (or copying) of the developed service models. In this sense, public services are in many countries also an important “market” for private innovations. For instance, in most Western economies, public spending constitutes about 30-50% of GDP.

- Public sector organizational innovation: these are efforts to create Weber Type I experimental organizations (such as the i-labs today) in order to answer specific new policy challenges. Indeed, ever since Weber, the smartest governments have maintained a healthy self-criticism of their own knowledge and capacities and left “slack” in government for learning and experimentation.

Thus, we have what seems a very important duality for understanding innovating bureaucracies: first, Weber Type I organizations based on the charisma and ideas of extraordinary individuals, and second, Weber Type II organizations based on expert knowledge and the authority of political backing. Both types can be beneficial for different policy goals. Weber Type I organizations are often good at experimenting in the small scale and coming up with new ideas and solutions, but they often need Weber Type II organizations to deliver these ideas and solutions on the scale of societal demand. In sum, either type can deliver different public sector innovation functions and play a role in enabling private sector innovations. Dynamic and innovative societies do not necessarily have to substitute traditional expert bureaucracies with experimental organizations. Instead, they need to complement expert bureaucracies with experimental organizations while constantly modernizing the skills and policy intelligence of expert bureaucracies.